Grandparents are generally less likely to work than non-grandparents. However, we do not know whether grandchild care provision is incompatible with grandparents’ employment. As the result from my recent study suggest, whether or not the two activities are in conflict may depend on the policy context where grandparents live.

European grandparents are important providers of care to their grandchildren. In the 2015 round of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), nearly half (45%) of grandparents reported looking after grandchildren, and nearly one fifth (18.5%) of those providing care reported doing so “almost daily”. Across Europe, cuts to public childcare services and subsidies in the last ten years have put mounting pressure on grandparents to provide daily childcare. At the same time, many European countries have implemented reforms to delay retirement in order to minimise the economic and budgetary costs associated with population ageing. Given these policy trends, it is timely to study how grandchild care provision relates to employment among European grandparents: if intensive grandchild care is incompatible with (full-time) work, shrinking levels of public support to childcare may be in contrast with the policy goal of extending working lives.

Previous studies have found that becoming a grandparent reduces both the probability of working as well as average working time. However, we know little about whether intensive grandchild care is in direct conflict with employment among grandparents. On the one hand, grandparents who choose to provide care may be less likely to work than those who choose not to, simply because they differ in their preferences towards family-based and work activities. On the other hand, daily grandchild care provision may be incompatible with employment, prompting grandparents with substantial care responsibilities to quit employment or work fewer hours.

Importantly, the presence of direct conflict between daily grandchild care and employment may depend on the context where grandparents live. In countries where public childcare services and subsidies are more generous, families are relieved of care responsibilities. In these contexts, providing daily grandchild care may be a matter of personal preference (e.g. common among family-oriented individuals), and grandchild care is unlikely to be conflict with grandparents’ employment. By contrast, in countries where families are heavily relied upon for the care of young children, working mothers may need to rely heavily on grandparents for childcare. This is likely to generate conflict between looking after grandchildren and grandparents’ employment.

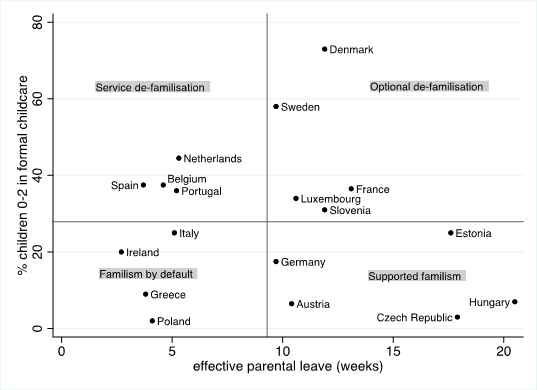

In a recent study using SHARE, I investigated the association between daily grandchild care provision and two employment outcomes for grandmothers and grandfathers aged 50–69: the probability of being employed and the average weekly working hours. Using a simultaneous equations approach, I was able to account for unobserved grandparent characteristics, such as personality traits, that may confound the association between grandchild care and employment. This allowed me to isolate any negative association between the two activities that is attributable to “direct conflict” between them. I used SHARE data from 18 countries: Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, and Sweden. In order to test whether the direct association between grandchild care and employment differs across policy contexts, I divided countries into four groups, defined by two childcare policy indicators: the proportion of children enrolled in public childcare services, and the effective number of weeks of paid parental leave (Figure 1).

Each group is characterised by different underlying assumptions about the role of families in the care of young children:

- Optional de-familisation: there is no expectation on families to provide intensive childcare, as childcare services are widespread; however, parental leave schemes are generous, giving parents the option to provide care themselves.

- Service de-familisation: families are relieved from care responsibilities through childcare services, but restrictive parental leave may mean that grandparental care is needed to complement services.

- Supported familism: service provision is low, leaving it up to families to look after children. The state explicitly supports the family care role through generous parental leave schemes.

- Familism by default: families are implicitly assumed to be responsible for care to young children, as neither services nor leave are extensively provided.

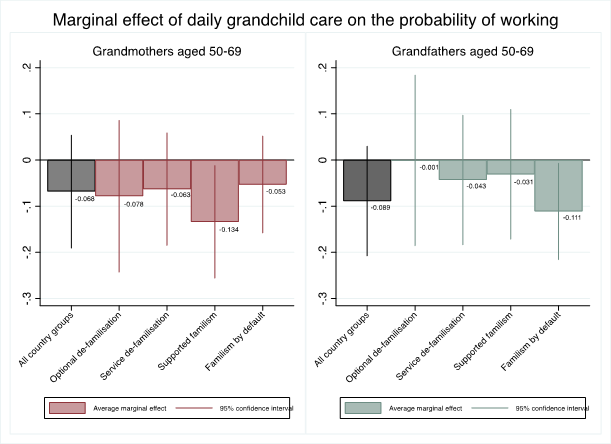

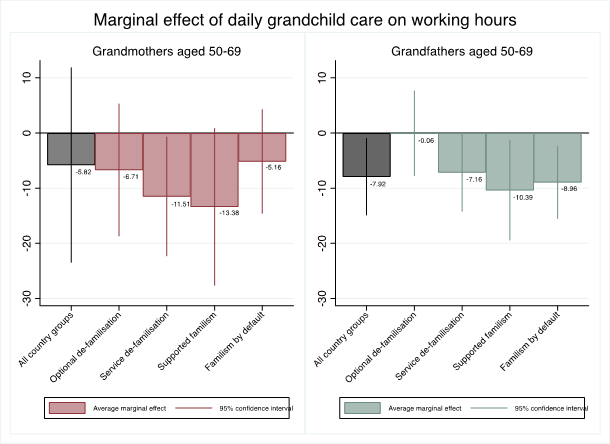

So what did the analyses reveal? Figure 2 describes the average change in the probability of working associated with providing daily grandchild care, while Figure 3 represents the average change in weekly working hours. “Average marginal effects” are reported alongside their 95% confidence intervals, which indicate whether the marginal effects are statistically different from zero. Overall, I found little evidence of any direct conflict between daily grandchild care and employment when all countries were considered (see the black bars in Figures 2 and 3). The only significant result was a marginal reduction in working hours for grandfathers, by eight hours per week.

However, some interesting differences emerged when I compared the four country groups identified above. In countries characterised by optional de-familisation, I found no association between the two activities, suggesting that grandparents who provide daily childcare are doing so out of personal preference (without role conflict). By contrast, conflict between the two activities was greatest in countries characterised by supported familism. In these contexts, strong public support for family care may lead working mothers to rely heavily on grandparents, potentially generating conflict between grandchild care and employment. Interestingly, there was no evidence of a negative association between grandchild care and employment for grandmothers in familism by default settings. This, however, is likely explained by the fact that very few grandmothers are active in the labour force in this group of countries.

Across Europe, policy reforms should acknowledge grandparents’ role as intensive childcare providers. Governments should aim to minimise potential conflicts with employment by providing affordable childcare services.

About the author:

Ginevra Floridi, Department of Global Health & Social Medicine King’s College London

This article is based on:

Floridi, G. (2020): Daily grandchild care and grandparents’ employment: A comparison of four European childcare policy regimes. Ageing & Society, 1-32. DOI: 10.1017/S0144686X20000987

Leave A Comment