Child care by grandmothers is a topic of great interest to social scientists and growing importance for policy makers. Maternal and paternal grandmothers don’t contribute identically, and patterns of caregiving are changing. SHARE illuminates these matters, as illustrated here by differences in grandmaternal care between rural Greece and elsewhere in Europe.

Maternal grandmothers are special

According to anthropologists and other students of family relations, maternal grandmothers typically provide more child care assistance than paternal grandmothers. Using data from Wave 2 of the Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), Mirkka Danielsbacka and her colleagues (2011) have shown that this “matrilineal” bias in how grandmothers direct their efforts is ubiquitous throughout Europe. A cross-cultural review has led us to conclude that it prevails almost everywhere (Daly & Perry 2017).

Exceptions are apparently confined to societies in whichnew brides leave their parents’ home and take up residence with the husband’s family, which limits the availability of maternal grandmothers as childminders. However, in many such societies, ranging from peasant farmers in Bangladesh to nomadic herders in Africa, women still rely on their own mothers for crucial assistance at childbirth, and while paternal grandmothers do more baby-sitting, it is the maternal grandmother who actually helps most when proximity is the same. Finally, a variety of evidence indicates that the presence of a maternal grandmother contributes to child survival and well-being more consistently than is the case for paternal grandmothers, which can be interpreted as further evidence that the former are more committed “investors” in their grandchildren.

Is rural Greece exceptional?

We have found only one published study in which grandmothers reportedly provided more care for their sons’ children than for those of daughters even when they lived equally far away. Pashos (2000) asked a sample of Greek adults how far away their grandparents had resided when they were small children and how much care each had provided. Among city-dwellers, maternal and paternal grandparents had dwelt equally far away, but the former were said to have provided more care. Rural residents, by contrast, had resided nearer to their paternal grandparents and recalled receiving more care from them. So far, these findings match those reported elsewhere, but a further analysis that led Pashos to conclude that rural grandmothers had provided more childcare for their sons’ children even when sons and daughters were equally near at hand.

This result was evidently unique, but the evidence could have been stronger. Pashos had coded living in the same household, in the same town, and even in “a neighboring village” as equally close. Would the finding that rural Greek grandmothers care preferentially for the children of their sons hold up if distance were differentiated more finely? And if so, would this Greek pattern of results prove to be truly exceptional, or might it be seen elsewhere in rural Europe? SHARE promised to provide some answers.

Urban versus rural Greek grandmothers: the SHARE data

In the standard SHARE interview, respondents are asked whether they have cared for any grandchildren in the absence of the parents, and if so, how often. (Our analyses were restricted to data from first-time interviewees, because only they are asked about care-giving within an invariant time frame, namely the preceding year.) Greece participated in Waves 1 and 2, then dropped out until Wave 6, so we began by analyzing data from Waves 1 and 2. Our first noteworthy finding was that Pashos’s results were indeed replicated. Urban Greek grandmothers cared more for the children of their daughters than for those of their sons, but the reverse was true in rural settings, regardless of differential proximity (Figure 1). Multivariate analyses, in which effects of proximity and the grandmother’s age, health, and numbers of “competing” grandchild sets were all controlled, demonstrated that the contrasting urban and rural preferences were both statistically significant.

If patrilineal practices and values persist mainly in rural areas, this pattern might apply beyond Greece. However, when we repeated our analysis for each of the fourteen European countries that had participated in SHARE Waves 1, 2, or both, the Greek results were unique.

And then something changed

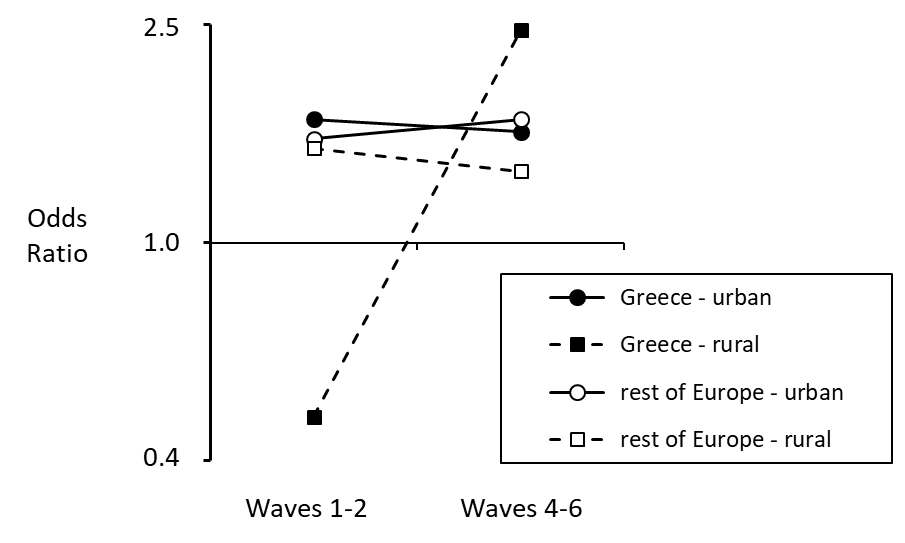

In SHARE Wave 6, Greece resumed participation, and something remarkable occurred: rural Greek grandmothers now exhibited the typical pattern of preferential care for daughters’ children. In fact, they did so especially strongly (see Figure 2). Importantly, these results are the outputs of analyses in which proximity and other potential confounds were controlled.

We suspect that the financial crisis of 2008-9, which hit Greece especially hard, played some role in this dramatic social change, but we could find no support for that hypothesis in additional analyses. We look forward to future research on how and why patterns of care are changing.

References:

Daly, M. & Perry, G. (2017) Matrilateral bias in human grandmothering. Frontiers in Sociolology, 2, 11. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2017.00011

Daly, M. & Perry, G. (2019) Grandmaternal childcare and kinship laterality. Is rural Greece exceptional? Evolution & Human Behavior, 40, 385-394. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2019.04.004

Danielsbacka, M., Tanskanen, A.O., Jokela, M. & Rotkirch, A. (2011) Grandparental child care in Europe: evidence for preferential investment in more certain kin. Evolutionary Psychology, 9, 3–24. doi: 10.1177/147470491100900102

Pashos, A. (2000) Does paternal uncertainty explain discriminative grandparental solicitude? A cross-cultural study in Greece and Germany. Evolution & Human Behavior, 21, 97–109. doi: 10.1016/S1090-5138(99)00030-6

About the authors:

Martin Daly is a Professor Emeritus in the Department of Psychology, Neuroscience & Behaviour, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

Gretchen Perry is an Associate Professor on the Department of Social Work, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand.

The article is based on:

Daly, M. & Perry, G. (2019) Grandmaternal childcare and kinship laterality. Is rural Greece exceptional? Evolution & Human Behavior, 40, 385-394. DOI: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2019.04.004

Leave A Comment