This paper explores how to measure successful aging in a manner consistent with the preferences of older persons about what matters in their lives. It considers the extent to which existing objective and subjective measures of successful aging reflect those preferences by proposing a new measure of successful aging consistent with those preferences. The implementation of the preference-based measure is illustrated with SHARE data for 11 European countries and shown to yield different results than existing objective and subjective measures on several terms.

The rapid aging of our societies poses formidable policy challenges in areas such as pensions, housing and social security. To evaluate the design and effectiveness of the policies concerned, it is essential that policy makers and researchers should have an operational yardstick for measuring the degree of “successful” aging.

Against the background of these diverse measures, an interesting question has come to the fore: who should define successful aging? We define objective measures very generally as all measures reflecting what the researcher or policy maker regards to be successful aging. Subjective measures, on the other hand, rely on direct judgments of the older persons about how successfully they are aging.

In this paper, we discuss the extent to which objective and subjective measures are consistent with the preferences of older persons with regard to what matters in their lives. To this end, we propose two litmus tests of respect for preferences. The first (intrapersonal) test ascertains whether a successful aging measure is consistent with an individual older person’s preferences regarding different life situations. The second (interpersonal) test scrutinizes whether measures of successful aging are consistent with preferences which would be unanimously held when older persons compare their life situations. Surprisingly, perhaps, we find that the objective approach fails the first test and that both approaches fail the second test. In this section, we first examine whether objective and subjective measures of successful aging adequately take into account what matters to older persons. To this end, we propose two litmus tests.

We propose an alternative and novel preference-based approach for measuring successful aging. Rather than to apply an algorithm chosen by the analyst, we rely on the preferences of the older persons. Contrary to what we see in the subjective approach, we do so without using the individual-specific and interpersonally incomparable satisfaction function, but rather by applying the underlying preferences directly. Individual preferences play a central role in the definition of the proposed measure. Our intuition therefore tells us that the first intrapersonal test of respect for preferences will be passed without any additional assumptions. Insofar as the second test is concerned, the problems caused by the lack of interpersonal comparability of the satisfaction functions can be sidestepped by relying on preferences rather than on the satisfaction function.

In the empirical implementation and comparison of the objective, subjective and preference-based measures of successful aging, we use data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) in waves 2, 4 and 5, which were collected in 2007, 2011, and 2013 respectively. We restrict the sample to the eleven European countries participating in all three waves of the SHARE survey: Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Switzerland, and Sweden. In these countries, we restrict the sample to respondents aged 60 or older for whom we possess all the necessary information to be able to compute the three measures of successful aging. To estimate the preference model, we use the following latent life satisfaction model:

In the first equation, the respondent compares her latent life satisfaction score with a series of personal reference values before deciding on a response. The second equation models the personal reference values which determine the use of the response scale. In the final equation, the score depends on the five dimensional description of the life situation of older person. Since different older persons may have different opinions about these weights, we allow the parameters to be different for different socio-demographic groups by including interaction terms between the five dimensions of life and indicators of the socio-demographic characteristics. The entire model is jointly estimated by maximizing its likelihood.

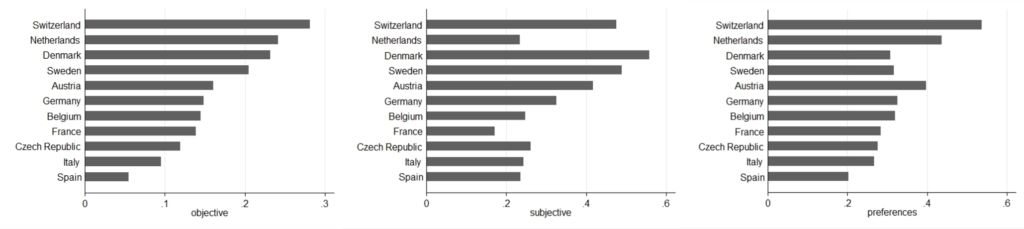

In Figure 1, we show the successful aging measurements for each of the countries concerned. The countries are ranked from top to bottom according to their objective successful aging scores. According to the objective scores, we can distinguish a frontrunner group consisting of Switzerland, The Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden; an intermediate group with Germany, Belgium, Austria and France, and a bottom group containing Spain, Italy and the Czech Republic. The Netherlands falls from the frontrunner group to the intermediate (or bottom) group when using the subjective measure; similarly France may be categorized among the lowest rather than the intermediate performers. The Scandinavian countries score worse with the preference-based measure.

Finally, we also look at the age distribution of successful aging. We find that older people tend to age less successfully according to the objective and preference-based measures. When looking at the subjective measure, we observe an irregular results pattern that spikes up and down around the same level of 32% until the age of 85, after which it declines. Underlying this unsteady pattern, there is again the complex interaction between the process of aging and the adjustment of references and expectations, previously referred to as the “satisfaction paradox”. These complex interactions lead to very different patterns. We observe a steady decline for Denmark, an increase for Switzerland, a stable pattern up until age 85 for Italy, and a remarkable increase up to age 80 followed by a decline for Belgium.

Our empirical investigations have shown that different measures offer a different perspective on successful aging in Europe in terms of its evolution over time, country rankings and age distribution. Successful aging measured by a subjective measure is highest in 2011 compared to 2007 and 2013, for instance, whereas the ranking is reversed for the objective and preference-based measures. These findings highlight the degree of importance we attribute to individual preferences in the measurement of successful aging, methodologically as well as empirically. Clearly, the choice of the measure is of great importance to draw precise policy conclusions about successful aging or simply to select exemplar countries.

About the authors:

Koen Decancq, Herman Deleeck Centre for Social Policy (CSB), University of Antwerp; Centre for Philosophy of Natural and Social Science, London School of Economics; CORE, Université Catholique de Louvain

Alexander Michiels, Centre for Social Policy, University of Antwerp, Belgium

The article is based on:

Decancq, Koen and Alexander Michiels (2019) Measuring successful aging with respect for preferences of older persons, Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 74(2), 364-372, https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx060.

Leave A Comment