Do early-life socioeconomic circumstances influence the level and the trajectories of health in old age? Do material and cultural aspects of socioeconomic disadvantage have the same impact on health? The current study aims to provide comprehensive answers to these questions.

Early-life socioeconomic circumstances and health trajectories

It is now established that the origins of poor adult health stem from early-life experiences, including socioeconomic circumstances (SEC). For instance, individuals who experienced disadvantaged SEC during early-life have lower levels of physical, cognitive, and emotional health functioning in old age. However, epidemiological evidences on the effects of early-life SEC on age-related decline in health outcomes are inconsistent. Some studies suggest that early-life SEC influence the rate of health decline, whereas other studies revealed no effects. Thus, whether early-life SEC are associated with the evolution of health in later life is still unclear.

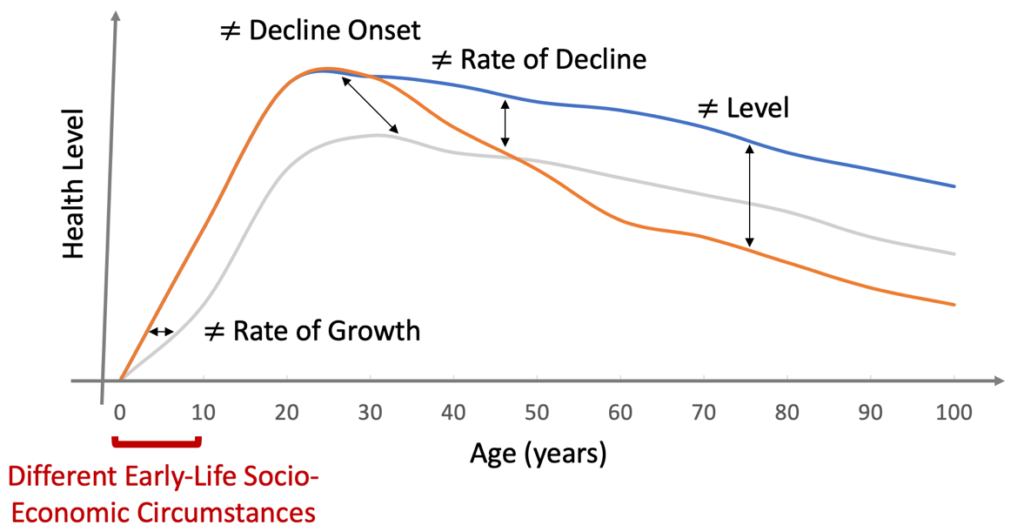

From an epidemiological viewpoint, the distinction between health level and its change across ageing is crucial because health in old age is expected to result both from the maximum health attained during early adult life and from the rate of decline over ageing. Indeed, various conceptual models in life-course research have been formulated (e.g., the Strachan-Sheikh model, the latency model, the pathway model, and the cumulative model) and, although they differ in the hypothesized mechanisms, they all suggest that events encountered in early-life, including socioeconomic ones, potentially influence both the level and the rate of decline of health in older age (Figure 1). As such assessing the links between early-life socioeconomic circumstances and health trajectories matters.

Theoretical influence of early-life SEC on health levels and their trajectories across ageing.

Why a lack of consistency between early-life socioeconomic circumstances and health trajectories?

Multiple factors may explain previous inconsistencies in the literature. First, studies mainly used on a unidimensional measure of early-life SEC (for example, focused only on father’s occupational position) or combined different dimensions of early-life SEC into a single score (for example, mixed together material and cultural aspects of socioeconomic disadvantage). This strategy may have biased (either inflate or deflate) the associations observed. Second, most previous studies only focused on one health outcome. Yet, the associations between early-life SEC and health may vary depending on the dimension of health assessed (e.g., physical, cognitive, emotional). Third, very few studies have assessed whether the associations between early-life SEC and health outcomes are independent from other early-life events likely to co-occur, such as adverse childhood experiences or childhood health problems. Fourth, when the data were longitudinal, the statistical approach used was not particularly suited to accurately estimate change over time. For example, studies with more than two occasions of measurement often adopted a statistical approach, namely accelerated longitudinal design, which artificially increased the noise when estimating the rate of decline over ageing.

Therefore, to fill this knowledge gap, the current study aims to determine whether individuals who experienced disadvantaged early-life SEC showed a steeper rate of health decline over ageing.

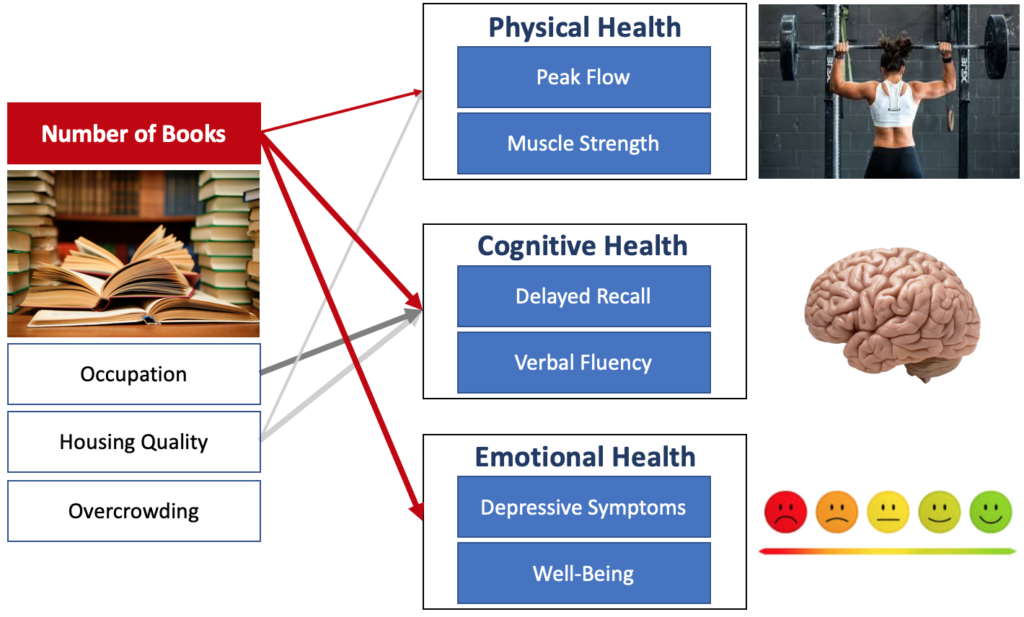

The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) We used data from more than 23,000 older adults from the survey of health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Number of books at home(0-10 vs. more books at home), overcrowding (more vs. less than one person per room in the household), occupational position of the household’s main breadwinner (first and second vs. higher skills levels of the International Standard Classification of Occupations), and housing quality (absence vs. presence of either fixed bath, cold running water supply, hot running water supply, inside toilet, or central heating) were used as indicators of early-life SEC. We investigated physical (muscle strength and lung function), cognitive (delayed recall and verbal fluency), and emotional (depressive symptoms and well-being) functioning as health-related outcomes (Figure 2). Finally, to further understand the potential long-lasting impact of early-life SEC, we also examined whether adult-life SEC factors (level of education, main occupational position during adult life, and satisfaction with household income) could neutralize the links between early-life SEC and health.

. The four dimensions of early-life socioeconomic circumstances

Number of books, health level, and health trajectories

Our results showed that early-life SEC impact the physical, cognitive, and emotional dimensions of health level in old age, even after adjusting for adult-life SEC factors. These findings corroborate the view that the etiology of health in older age is the result of multiple exposures encountered across the life course, with a critical role played by events arising in early life.

Crucially, the number of books at home during childhood (a cultural aspect of disadvantage) has a strong and wide influence on these three dimensions of health (Figure 3). By contrast, the material aspects of disadvantage seem to have more circumscribed effects. Additionally, our results showed that the etiology of a particular health status may be linked to specific dimensions of early-life disadvantage. For example, poor housing quality, which is associated with mould, dust, dampness, or microparticles, was strongly linked with poorer lung function in both men and women, but not with muscular function.

By contrast, evidence of the contribution of these early-life exposures to differences in health trajectories over time was weak. Hence, our study does not fully support the conceptual models in life-course research – the latency model, pathway model, cumulative model, and Strachan-Sheikh models – arguing a potential link between early-life SEC and health trajectories in older age. However, the absence of consistent effects of early-life SEC could contribute to shedding light on other critical predictors of healthy ageing trajectories. Conceptual models in life-course research should consider the possibility of limited influence of early-life SEC on healthy ageing trajectories.

The importance of books during childhood for multidimensional health in old age.

About the authors:

Boris Cheval, Post-doc researcher, Université de Genève, Faculté de psychologie et des sciences de l’éducation.

Matthieu Boisgontier, Associate Editor, Advances in Cognitive Psychology; Co-chair, Society for Transparency, Openness, and Replication in Kinesiology (STORK); Publication Board Member, STORK

Stéphane Cullati, Senior researcher, Université de Genève, Institut de démographie et socioéconomie

The article is based on:

Cheval B, Orsholits D, Sieber S, et al, Early-life socioeconomic circumstances explain health differences in old age, but not their evolution over time, J Epidemiol Community Health Published Online First: 09 April 2019. doi: 10.1136/jech-2019-212110

Leave A Comment