We disentangle the direct effect of health on employment and hours worked from its indirect effect that is mediated through wages. We find a large total effect of health on employment and hours worked which is attributable to the direct health effect and not to its indirect effect. This supports policies that accommodate older workers with health limitations through reduced job demands or a change of tasks.

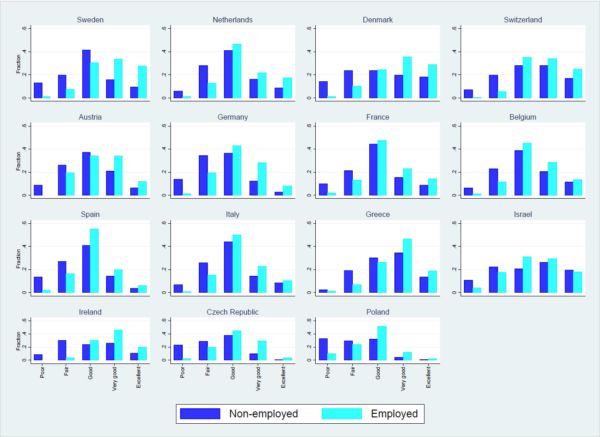

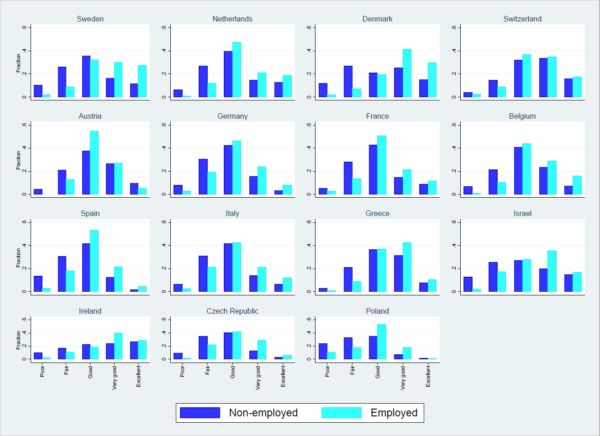

The fact that employed men and women aged 50 to 64 in 15 European countries report better health than their non-employed peers (see Figures 1 and 2) suggests that, as empirically supported in the literature, health plays an important role in explaining employment at older ages. In this paper, we add to this research by quantifying the role of individual wages in the health-employment nexus. Quantifying the mediating role of wages in the health-employment nexus is important for both understanding individuals’ labor market behavior and designing employment policies that support older workers with health limitations to stay employed. The direct effect of health on employment is related to the ability to work, which can be affected by, for instance, better accommodating workers with health impairments through reduced job demands or a change of tasks. Its indirect effect through wages, in contrast, indicates the degree to which it is financially worthwhile to remain employed, a decision that may be influenced by such initiatives as wage subsidies for workers with health impairments.

Figure 1 Distribution of self-reported health by employment status for men aged 50–64 years in Europe

Source: Author calculations based on waves 1 and 2 of SHARE. The figure shows the distribution of self-reported health (SRH) by employment status for men aged 50–64 years in 15 European countries. SRH is measured on a 5-point scale from poor to excellent health.

Figure 2 Distribution of self-reported health by employment status for women aged 50–64 years in Europe

Source: Author calculations based on waves 1 and 2 of SHARE. The figure shows the distribution of SRH by employment status for women aged 50–64 years in 15 European countries. SRH is measured on a 5-point scale from poor to excellent health.

Earlier studies have not disentangled health’s direct effect on employment from its indirect effect through wages and this may have led to an incorrect assessment of the hypothesized direct effect of health on employment and, consequently, of the importance of policies aimed at helping employers to accommodate workers with health limitations to keep them employed at older ages. We therefore estimate a system of equations for health, wages, employment and hours of work that enables a quantification of both the direct and indirect effects (through wages) of health on employment and hours worked. We thereby account for several difficulties. For instance, self-reported health (SRH) status, which we use to measure people’s health, can differ from true health, introducing a measurement error. Employment and wages can also affect health, and there may be unobserved factors – like personality traits – that affect both health and labor market outcomes in adulthood. Below we discuss the main results from our preferred specification where we account simultaneously for these issues. A broader discussion of the results and of other technical issues that we need to deal with when estimating our model can be found in the paper.

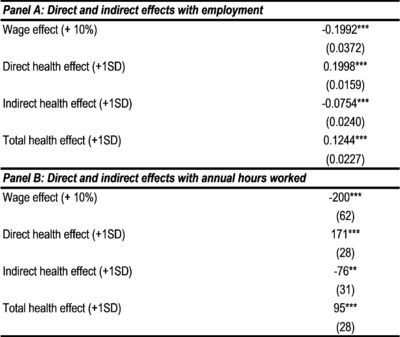

Our findings show that health has positive effects on wages, employment and hours worked (see table below and table II in the paper for the health effects on wages). In terms of a health deterioration, defined as a change in health from the 75th to the 50th percentile in the health distribution (or about a 1 SD change), our results in the table show that it leads for men to about a 12 percentage point lower employment probability (Panel A) and 95 fewer hours worked per year (Panel B), on average. These effects on the employment probability are the sum of a 20 percentage point direct negative effect and an indirect positive effect of about 8 percentage points (Panel A). Likewise, the effects on hours worked are the sum of a 171 hours negative direct effect and a 76 hours positive indirect effect (Panel B). These indirect effects have signs opposite to the signs of the direct effects because of negative wage effects on hours worked and employment (see Table II in the paper). This also suggests that ignoring wages in employment or hours equations leads to an underestimation of the direct health effects. Concerning the effects on hours, it needs to be noted, however, that they appear not robust to using a different specification for the hours equation (see paper for more details). The results for women are similar to those of men with the exception that their hours worked is more elastic with respect to wages which are themselves less (or no) responsive to health, resulting in relatively smaller indirect effects of health on hours worked and employment than that for men (see Table III in the paper).

Table 1: Direct and indirect effects on employment (0-1) and hours worked in our preferred specification. Results are for mena

Note: SD = Standard Deviation.

a Estimated marginal effects on employment probability and annual hours worked. Standard errors, in parentheses, are clustered at the individual level. Significance levels: *** p<0.01 ** p<0.05 * p<0.10. The results correspond to Model 5 in Table III. We refer to our paper for more details.

From a policy perspective, in particular the large direct effects of health on employment imply an instrumental role for policy aimed at helping employers accommodate workers with health limitations so as to keep them on the job at older ages. Such an inference is very much in line with recent calls from academia and international organizations such as the OECD for supported work over cash benefits for people with disabilities and, in particular, increased employer incentives to accommodate work-limited employees.

About the authors:

Manuel Flores, Research Institute for Evaluation and Public Policies (IRAPP), Universitat Internacional de Catalunya

Adriaan Kalwij, Utrecht University School of Economics

This article is based on:

Flores, M. and Kalwij, A. (2019). ‘What do wages add to the health-employment nexus? Evidence from older European workers’, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 81, pp. 123–145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/obes.12257

Leave A Comment