Retirement is often seen as a clear transition from employment to receiving a pension. However, this has changed over the last years since more and more Europeans work beyond retirement age. What drives those people to favour employment over retirement life? Our article contributes to the literature by relating working beyond retirement to the previous career of a person. The results suggest that previous part-time work and high occupational status as well as a flexible career with transitions in and out of employment increase the likelihood of working after retirement. Additionally, divorced women are more likely to work beyond retirement.

A decision to work after retirement does not occur instantly and secluded from other choices individuals make along their life. Previous research has mainly focused on factors proximal to the retirement transition, such as health, wealth, and income level at the time of the retirement process. While the studies that introduced those factors have partially brought the whole complexity of this novel social phenomenon to light, they have neglected the impact of retirees’ work experiences accumulated over the life course.

Life course theory, adopted in our study, suggests to include previous labour market experience when uncovering the determinants of working after retirement. From this perspective, retirees’ accumulated work experience, work-related networks, and pension entitlements are seen as a result of the work history that sets the opportunity structure for working after retirement. Previous research mainly followed the hypothesis that individuals might be pushed into working after retirement for financial reasons. In fact, financial constrains in old age arise from incapacities to accumulate sufficient resources during their working life. For example, older persons who have been mainly engaged in part-time or low-status work during their career would need to compensate for sparse pension entitlements by working beyond retirement age. Also, individuals with discontinuous careers might be pushed into working after retirement due to financial constraints arising from fragmented previous earnings. Furthermore, divorced women could be seen as one of the most disadvantaged groups with regard to pension right accumulation as they most likely have discontinued work experience due to the provision of unpaid care work during their former marriage, but at the same time lack a second income in the household when they are old.

However, besides the fact that individuals might have to continue working, we also have to consider who is able and motivated and has opportunities to do so. Therefore, working beyond retirement age might be an option for individuals with a high level of labour market integration and work commitment – not necessarily for financial reasons. In contrast to those with interrupted careers and in low status jobs, individuals who have worked full-time most of their life accumulated more work experience and skills. Additionally, individuals who have been self-employed and/or in a position with high occupational status are seen as more committed and autonomous at completing job tasks by potential employers, thus they will have more opportunities to work after retirement. Frequent job changes might also generate opportunities for working beyond retirement as individuals have generated ties to many employers and have shown to be flexible.

To test our hypotheses, we have used five waves of the ‘Survey of Health, Aging and Retirement in Europe’ (SHARE), from 2004, 2006, 2008, 2011, and 2013 respectively. This data includes information on adults aged 50 years and older in several European countries. The third wave of SHARE, better known as SHARELIFE (2008), includes retrospective information on the respondents – namely, job history and family life, collected using a Life History Calendar approach. We use this information to describe the work-life path of individuals for the age-span 20 to 59. The final sample included 19,283 observations nested in 11,369 retired individuals aged between 60 and 75 from 13 countries.

For our primary analysis, we used multilevel logistic models with country fixed effects to compute odds ratios of working beyond retirement age. All estimations were executed separately by gender. We examine a set of possible determinants of working after retirement related to the work history – namely, years in full-, part-time and self-employment, number of jobs, previous occupational status (derived from the International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status) – as well as previous divorce. Present marital, health and educational statuses, age, pension income per household are controlled.

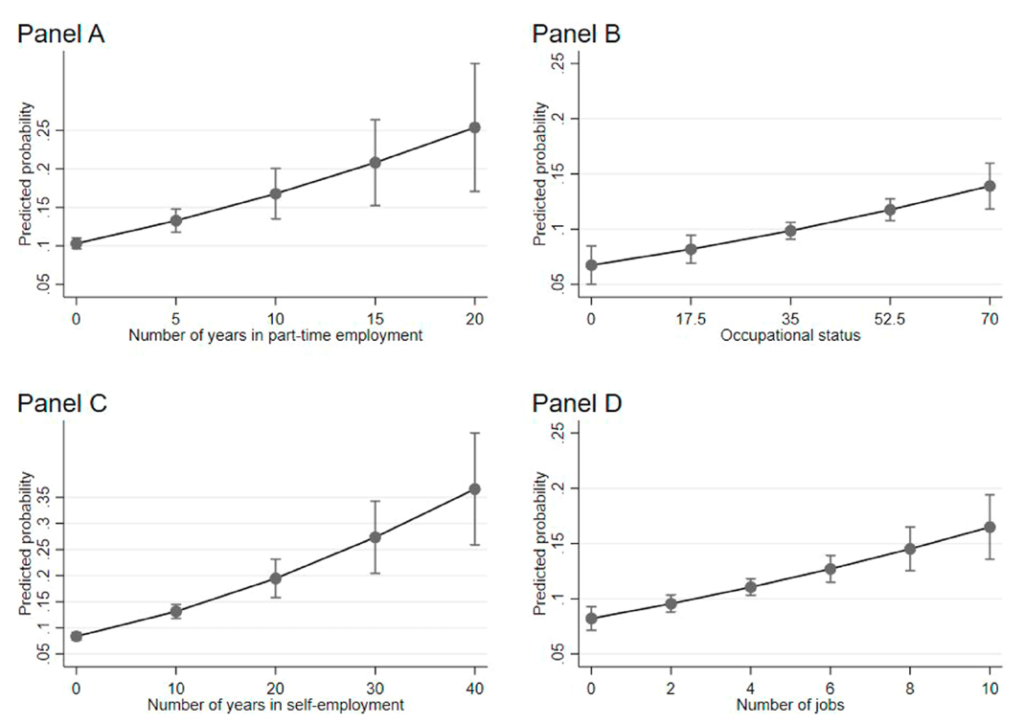

Figure 1: Predicted probability of working after retirement according to different values of working history indicators for women aged 60–75 years.

Note: calculation based on multilevel logit models.

Source: own calculations using SHARELIFE and SHARE waves 1-5

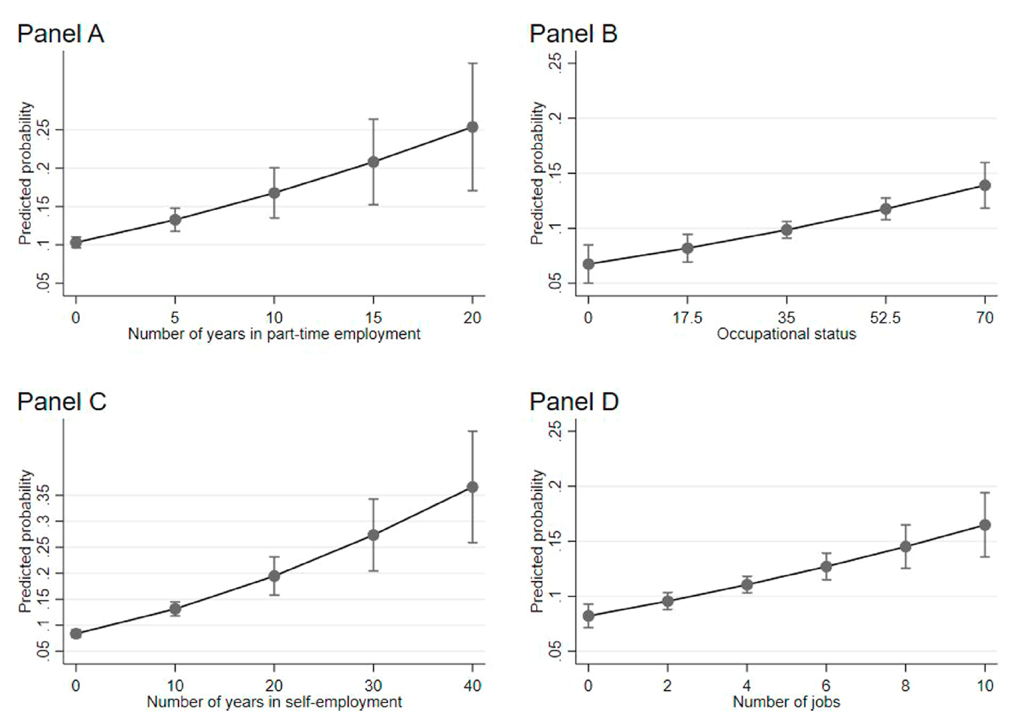

Figure 2: Predicted probability of working after retirement according to different values of working history indicators for men aged 60–75 years.

Note: calculation based on multilevel logit models.

Source: own calculations using SHARELIFE and SHARE waves 1-5.

From our logistic models, as hypothesized, we found that part-time work is positively linked to a higher chance of working in retirement. Moreover, its effect is just slightly stronger for men than for women, as the additional income from a paid job in retirement can indeed supplement the possible gaps of financial resources. Interestingly, for women – not for men – each year of full-time work is associated with an increase in chances to adopt a working-after-retirement strategy (see Figure 1).

Additionally, the results show that higher occupational status is related to a higher likelihood of employment in retirement for male retirees (see Figure 2), while for women we do not find a significant relationship between both factors. Self-employment is indeed positively associated with the probability of working after retirement for both genders. The same applies to the number of jobs as an indicator of career flexibility: the more job changes, the more likely is working in retirement for both genders. Lastly, concerning marital status, divorced women have a higher probability of working after retirement compared to their married and re-married counterparts.

All in all, the results of our study are consistent with the premise of life course theory. The work trajectory of an individual indeed sets the opportunity structure for the decisions on work behaviour after retirement. It is not only financial constrains due to previous non-standard employment or divorce that “pushes” retirees into working. Also, those with previously flexible careers or high-status jobs are more likely to work beyond retirement – this suggests that not only the necessity, but also the opportunities and work attitude are of importance. This may generate inequality and sets new policy challenges: the policy to prolong working lives as currently implemented in many European countries could disproportionately favour individuals who have benefited throughout their work careers as they have better opportunities to extend their working activities. In contrast, for individuals who experience the decline of health and productivity it could become a struggle. Moreover, the increase in work career and family life discontinuity along with the shift towards more individual responsibility for pension provision generates even more policy challenges. Therefore, policy makers should direct their attention to the accumulation of pension entitlements and savings by individuals in low-status jobs, with diverse and discontinuous career paths.

About the authors:

Ellen Dingemans, Institute Het PON, Tilburg, Netherlands

Katja Möhring, Chair for Macrosociology , University of Mannheim, Germany

The article is based on:

Dingemans, E., & Möhring, K. (2019). A life course perspective on working after retirement: What role does the work history play? Advances in Life Course Research, 39, 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2019.02.004

Leave A Comment