I analyze unusually rich data derived from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) and from other sources to assess the impact of access to prescription drugs on disability from 31 diseases in eleven European countries. My findings show the reduction in the average disability of living people due to new drug launches would probably have been even greater if the drugs had not reduced mortality.

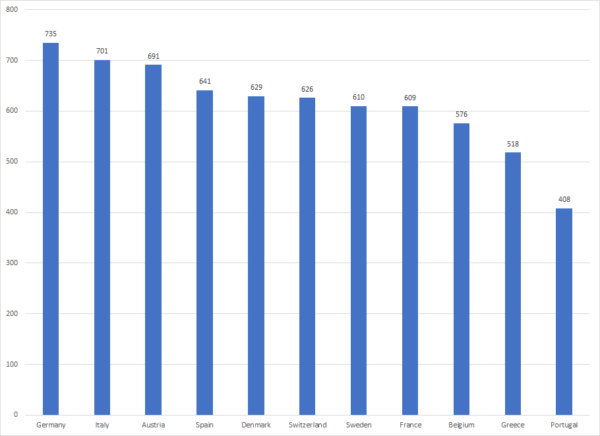

Clinical studies have shown that the use of certain drugs can reduce disability. Access to prescription drugs varies across countries. Figure 1 shows the number of new chemical entities (NCEs) that were launched in eleven European countries during the period 1982-2015. The average number of NCEs launched in the top 3 countries (709) was 42% higher than the number of NCEs launched in the bottom 3 countries (501).

Figure 1: Number of New Chemical Entities launched during 1982-2015, by country

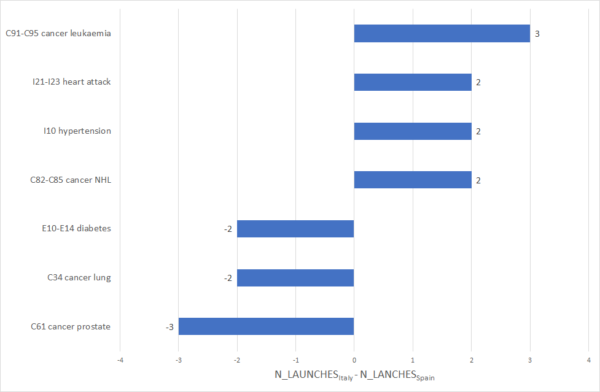

Even when the total number of drugs launched in two countries is similar, the specific drugs that were launched, and the diseases those drugs are used to treat, may differ. As shown in Figure 2, at least two more drugs were launched in Italy than in Spain for four diseases, and at least two fewer drugs were launched in Italy for three other diseases. My study showed that the relative number of drugs launched for a disease in a country is higher when the relative prevalence of that disease is greater: “misery loves company.”

Figure 2: Difference between number of drugs launched during 1982-2015 for 7 diseases in Italy and Spain

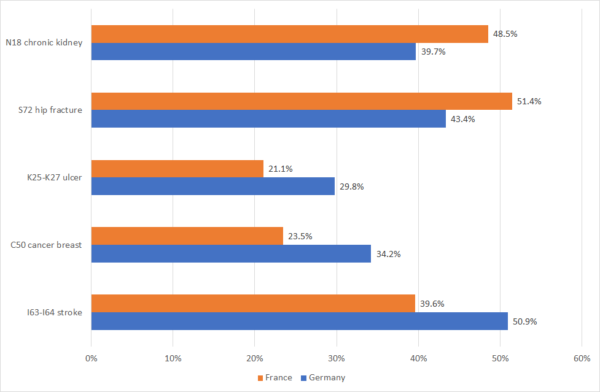

As shown in Figure 3, relative disability from different diseases varies across countries: French people who had had chronic kidney disease and hip fractures were more likely to be severely limited than Germans, but French people who had had ulcers, breast cancer, and strokes were less likely to be severely limited than Germans.

Figure 3: Percent of people in France and Germany in 2015 with 5 medical conditions who were severely limited

In a recent paper, I tested the hypothesis that the larger the relative number of drugs for a disease that were launched during 1982-2015 in a country, the lower the relative disability in 2015 of patients with that disease in that country, controlling for the average level of disability in that country and from that disease, and the number of patients with the disease and their mean age. I analyzed several measures of disability for 31 diseases in eleven European countries using data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) and from other sources.

The estimates implied that drug launches during 1982-2015 reduced the probability of severe limitation in 2015 by 4.9 percentage points, from 21.8% to 16.9%; they reduced the probability of any limitation by 7.7 percentage points, from 61.1% to 53.4%; and they reduced the mean number of Activities of Daily Living limitations by about 29%. Drug launches also yielded a small increase in an index of quality of life and well-being.

I estimate that mean pharmaceutical expenditure on drugs launched after 1981 by people 45 and over in the eleven European countries was $611. Expenditure of $611 reduced the probability of being severely limited by 4.9 percentage points. If people would have been willing to pay at least $12,469 (= $611 / 4.9%) to avoid being severely limited, which is very likely, drugs launched during 1982-2015 would have been cost-effective, even if they did not provide any other benefits, e.g. increased longevity and reduced hospitalization. However previous research has demonstrated that new drug launches have also provided those benefits.

In general, the larger the number of drugs for a disease that were launched during 1982-2015 in a country, the lower the average disability in 2015 of patients with that disease in that country, controlling for the average level of disability in each country and from each disease, and the number of patients with the disease and their mean age.

The long-term reduction in disability attributable to increasing availability of prescription drugs may have been offset by adverse trends in behavioral risk factors, such as obesity. SHARE data indicate that the fraction of the population aged 50 and over that was obese (BMI > 30) increased from 17.1% in 2004 to 22.2% in 2015.

Previous research has demonstrated that new drug launches have reduced mortality: they have enabled people who would have died if the drugs had not been launched to remain alive. Presumably, those additional survivors were the most severely ill and disabled: biomedical innovation tends to offset natural selection. Therefore, the reduction in the average disability of living people due to new drug launches would probably have been even greater if the drugs had not reduced mortality.

About the author:

Frank R. Lichtenberg, PhD, Columbia University, National Bureau of Economic Research, and CESifo

The article is based on:

Lichtenberg FR, The impact of access to prescription drugs on disability in eleven European countries, Disability and Health Journal, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2019.01.003.

Leave A Comment