Does poor health influence one’s material situation and social relations? Or is the relationship reverse, with individuals in difficult material and social conditions facing higher risks of health deterioration?

Uncovering the causal components in the relationship between health and material and social conditions seems to be one of the more challenging problems in many microeconomic and epidemiological studies (to name just a few: Adena and Myck, 2014; Benach et al., 2001; Carstairs & Morris, 1989; Doebler and Glasgow, 2017; Miyawaki, 2015; Rohde et al., 2017; Yur’yev et al., 2010). Health outcomes and material and social circumstances are so tightly intertwined and so strongly result from common factors such as individual characteristics and the entire life history, including childhood conditions, that providing a clean causal identification is extremely difficult, if at all possible.

We take up the challenge in a recent paper based on the data from waves 5 and 6 of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), collected in 2013 and 2015 respectively. The high level of detail in the data and the panel structure of SHARE allow us to take a very careful approach to minimize the extent of the endogeneity bias in the relationship between health and material and social conditions. To do that, first, we examine the relationship with respect to changes in health status between two points in time. Second, to control for the factors which may be considered as characteristics jointly determining late-life health and socioeconomic outcomes, we take advantage of the richness of SHARE data by extending the model to include a long range of variables relating to childhood conditions available for many respondents, such as family socio-economic situation, performance at school or health status at age 10. Finally, we control for the levels in additional health dimensions at time t-1 (such as hand grip strength or chronic diseases) to account for the correlation of material and social conditions with health status at the initial point in time.

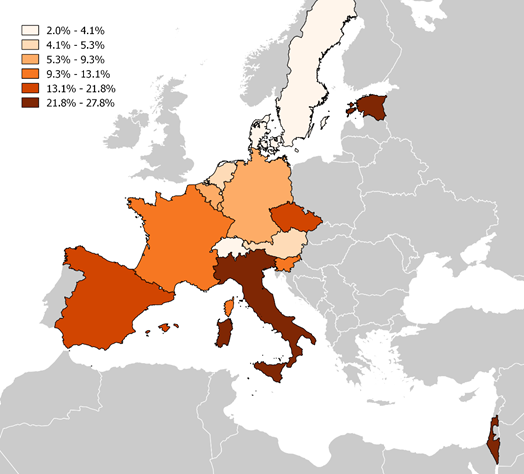

In the study we rely on the concepts of material and social deprivation and social exclusion proposed in Myck et al. (2015), specifically designed for the purpose of the SHARE survey. The authors compile two complex and comprehensive indices of material and social deprivation that reflect disadvantages in broad aspects of wellbeing in later life including material conditions, quality of neighbourhood and accessibility to services. On top of that, individuals severely deprived in both dimensions are identified as being at risk of social exclusion. In Figure 1, we present the percentage of population at risk of social exclusion in selected countries. The diversity within Europe is striking – while only 2% of the Danish 50+ population is identified as socially excluded, this share increases to as much as 25% in Italy and even 28% in Estonia.

Source: Myck et al., 2019.

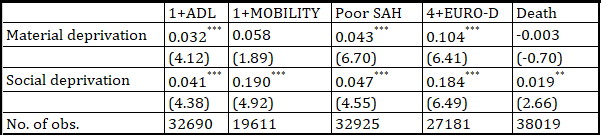

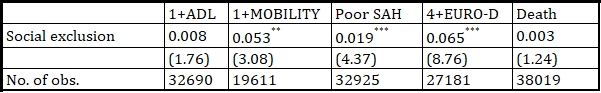

These indicators of material and social circumstances are related to three measures of physical health, a measure of mental health and the likelihood of dying. Physical health is assessed through difficulties with everyday life activities (ADL), mobility impairments (MOBILITY) and self-reported poor health. We measure mental health using the EURO-D scale, and the likelihood of dying is based on the end-of-life information recorded in the survey.

Table 1. Role of material and social deprivation for the probability of change from good to bad health between SHARE wave 5 and wave 6 (marginal effects)

Notes: t statistics in parentheses; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. We run regressions for each health dimension separately. Controls include demographic information, childhood fixed effects and health controls in time t-1. “Poor SAH” – self-reported poor health. By change from good to bad health we mean e.g. change from having no difficulties with ADLs in wave 5 and reporting 1+ difficulties with ADLs in wave 6.

Source: Myck et al., 2019.

Table 2. Role of social exclusion for the probability of change from good to bad health between SHARE wave 5 and wave 6 (marginal effects)

Notes and source: see Table 1.

Tables 1 and 2 present a brief summary of the results of our estimations, separately for the impact of material and social conditions on health deterioration (Table 1) and the effects of social exclusion (Table 2). Full results are available in Myck et al. (2019). The estimates for our results for all measures of physical and mental health suggest a strong and statistically significant relationship between the indicators of deprivation and social exclusion and health. Interestingly, we find however that probability of dying between waves 5 and 6 of SHARE is only affected by social and not by material deprivation.

Our study thus confirms earlier findings that material and social conditions in old age have their likely causal implications for the development of health status. The results extend beyond the existing research and provide evidence that the two dimensions of deprivation – material and social, might affect people differently with respect to different measures of health. It seems informative to include the two separate indices of deprivation, rather than the combined indicator for social exclusion, as the combined index would conceal important heterogeneity in effects of the different dimensions. The results are of potentially high relevance from the policy perspective, as examination of the specific role of material and social deprivation for developments in health at a later stage in people’s lives can be instrumental in designing specifically targeted policy interventions. Along these lines, understanding of negative health developments among the currently deprived population may serve as an important sign of future developments in the level of health and health care needs, providing policy makers with expectations for the future needs and the resulting costs. It also highlights positive health implications of reducing material and social deprivation in old age.

About the authors:

Michał Myck, Director of the Centre for Economic Analysis CenEA (Poland)

Mateusz Najsztub, Senior Research Economist at the Centre for Economic Analysis CenEA (Poland)

Monika Oczkowska, Senior Research Economist at the Centre for Economic Analysis CenEA (Poland)

The article is based on:

Myck, M., Najsztub, M., Oczkowska, M. (2019), Journal of Ageing & Health (2019). https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264319826417

Leave A Comment