We examined bidirectional, time-ordered associations between age-related changes in depressive symptoms and memory. Depressive symptoms increased and memory scores decreased across the observed age range, with worsening mostly evident after age 62 years. In later adulthood, lower memory performance at a given age predicts subsequent 2-year increases in depressive symptoms.

Two worrisome conditions related to ageing are memory loss and declining emotional wellbeing. The good news is that most older adults will likely only experience relatively mild declines in cognitive ability and wellbeing in later life, whereas a relatively small percentage will experience clinically diagnostic mental impairment or depression. Regardless of severity, we know that age-related reductions in cognitive ability and emotional wellbeing are closely related.

This leads to questions about whether such changes depend on a common underlying condition, such as worsening physical health or bereavement, whether lower cognitive ability precedes declines in emotional wellbeing, or whether worsening emotional health provokes cognitive impairment. For example, vascular diseases and related losses in cerebral white matter (brain) tissue are linked both to poorer cognitive ability and increased symptoms of depression. There is also evidence that long-term neuroendocrine changes linked to anxiety and depression can suppress memory function. Additionally, age-related decrements in cognitive ability may lead to increased difficulty in activities of daily life, such as management of personal finances and social relations—which in turn provokes increased depression risk. These scenarios are not mutually-exclusive, and each may be present to a varying extent across different windows of the adult life span.

A better understanding of how associations between age-related changes in memory and depressive symptoms unfold across time may facilitate early diagnosis and prevention of potentially more severe worsening in mental health later on. Toward this end, we looked at reciprocal relations between multi-year changes in memory and depressive symptoms using data from more than 107,000 SHARE participants, whose ages ranged from 50 to 90 years and who represented 21 countries.

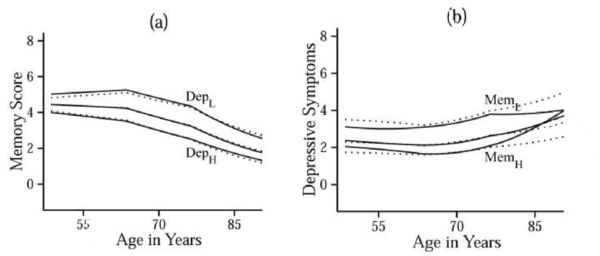

We found that, on average, depressive symptoms increased and memory scores decreased across the observed 40-year age range, with worsening most apparent after age 62 years. For most individuals, memory decline and depressive symptoms remained beneath the cut-offs for clinical severity until late in life (i.e., following age 85 years). Persons with poorer memory generally had higher levels of depressive symptoms across this period, but these differences became less apparent following age 80 years as individuals with initially better levels of memory and wellbeing showed accelerated worsening later in life.

Figure: Panel (a) shows trajectories of estimated memory scores within sub-samples of participants with different baseline levels of depressive symptoms: low (≤ -1.5SD; DepL), mid (> -1.5SD and < 1.5SD; unlabeled), and high (≥ 1.5SD; DepH). Panel (b) shows trajectories of estimated depressive symptoms within sub-samples of participants with different baseline levels of memory scores: low (≤ -1.5SD; MemL), mid (> -1.5SD and < 1.5SD; unlabeled), and high (≥ 1.5SD; MemH). Solid lines indicate trajectories estimated from the full coupling model, and dotted lines are trajectories estimated from the nocoupling model.

Beyond these general long-term changes, the study showed a time-ordered association such that poorer memory performance at a given age predicted worsening in depressive symptoms across the subsequent 2-year interval, whereas elevated depressive symptoms at a given age did not predict subsequent decline in memory. Statistically, each 1-point decrement on a 10-point memory scale at a given age predicted a 14.5% increased risk for depression two years later. This association did not appear to be affected by differences in sex (men vs. women), education level, smoking, or being overweight. This outcome replicates a similar finding from a large-sample study of older adults in the United States. There is, however, much yet to learn about temporal associations between age-related changes in cognition and depressive symptoms, especially across shorter time scales (e.g., daily, weekly, monthly).

So why does this matter? Well, it may be that pro-active monitoring for cognitive decrements in later life can expedite interventions to reduce associated increases in depression risk. That is, if cognitive decline is, to some extent, inevitable in life, perhaps steps can be taken to maximize wellbeing in the face of such decline—by, for example, providing increased functional and/or social support prior to the need for clinical intervention. We hope in the future to see more studies to identify useful strategies for providing such support to older adults experiencing cognitive impairment in their day-to-day lives.

The article is based on:

Aichele, S., Ghisletta, P. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2018 Jan 29. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx183

About the authors:

Stephen Aichele, Swiss National Center of Competence in Research LIVES-Overcoming vulnerability: Life course perspectives, Universities of Lausanne and of Geneva, Switzerland.

Paolo Ghisletta, Swiss National Center of Competence in Research LIVES-Overcoming vulnerability: Life course perspectives, Universities of Lausanne and of Geneva, Switzerland; Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, University of Geneva, Switzerland; Swiss Distance Learning University, Switzerland.

Leave A Comment