There are gender differences in cognition across countries, but what are the causal drivers? Gender differences in cognition are the result of biopsychosocial interactions throughout the life course. Social-cognitive theory of gender development posits that gender roles may play an important mediating role in these interactions. We find that older women performed relatively better in countries characterized by more equal gender-role attitudes. The effect was partially mediated by education and labor-force participation. Cognition in later life thus cannot be fully understood without reference to the opportunity structures that sociocultural environments do (or do not) provide.

Our study analysed whether women’s cognitive functioning past middle age may be affected by the degree of gender equality in the country they live in. This research is a first attempt to shed light on important, but understudied, adverse consequences of gender inequality on women’s health in later life. It shows that women living in gender-equal countries have better cognitive test scores later in life than women living in gender-unequal societies. Moreover, in countries that became more gender-equal over time, women’s cognitive performance improved relative to men’s.

While economic and socioeconomic factors likely play an important role, sociocultural factors such as attitudes about gender roles might also contribute to the variation in gender differences in cognitive performance around the globe. The hypothesis of this study was that women who live in a society with more traditional attitudes about gender roles would likely have less access to opportunities for education and employment and would, therefore, show lower cognitive performance later in life compared with men of the same age.

We tested this hypothesis using representative samples of individuals aged 50 and above from 27 countries. The sample included 226,661 observations of individuals born between 1920 and 1959 and come from comparable surveys: the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), the English Longitudinal Study on Ageing (ELSA), and the World Health Organization Study on Global AGEing and Adult Health (SAGE). All surveys include an episodic memory task to measure cognitive performance. Participants heard a list of 10 words and were asked to recall as many as they could immediately. Additionally, some of the surveys included a task intended to assess executive function in which participants named as many animals as they could within 1 minute. To gauge gender-role attitudes, we used data from the World Values Survey that include self-reported agreement with the statement, “When jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women.”

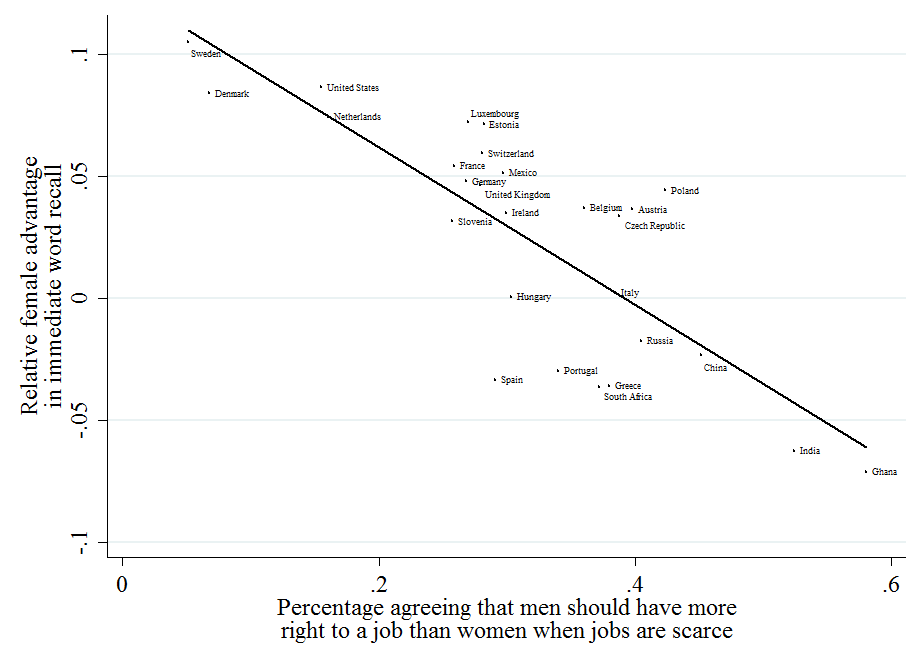

Our results first show that gender differences in cognitive skills in later life vary considerably across countries. Second, we find that gender differences in cognitive skills across countries are highly correlated with gender-role attitudes: women living in countries characterized by traditional gender-role attitudes perform worse (relative to men) than in countries characterized by more egalitarian gender-role attitudes. The following Figure shows the relationship between the relative female advantage in cognitive performance (measured by an immediate word recall test score) and a measure of gender-role attitudes. This Figure shows indeed that the relative female advantage in cognitive performance varied significantly across countries (on the vertical axis). The relative female advantage varied from -7.1% for Ghana to +10.5% in Sweden. It also shows a strong negative association between the degree of traditionalism displayed in gender-role attitudes and the relative female advantage in immediate word recall across the 27 countries included in our study. As expected, we found that across countries less traditional gender-role attitudes were associated with better female cognitive performance in later life (i.e., immediate recall). This association remained unchanged if we control for the differences in the economic development across countries (measured by the Gross Domestic Product per capita).

Fig.1: Negative cross-country association between relative female advantage in immediate word recall and the percentage of individuals born between 1920 and 1959 agreeing with a statement that men should have more right to a job when jobs are scarce

Data source: SHARE, HRS, ELSA, SAGE for immediate word recall and WVS for the percentage of individuals born between 1920 and 1959 agreeing with a statement that men should have more right to a job when jobs are scarce. The relative female advantage in cognitive test score (∆C) is equal to (Cf – Cm)/ Cm, where Cf and Cm are the average cognitive test scores of women and men, respectively.

We extended our analysis by showing that gender differences in cognitive skills not only vary across countries but also across cohorts within countries, and those variations are correlated to cohort-related changes in gender-role attitudes within countries. Further analyses suggested that this association is unlikely to be driven by reverse causality. Finally, we explored the potential mechanisms by looking at the role of education and labour market participation during the life course in explaining gender differences in cognitive skills across countries and cohorts. Those two factors accounted for about 30 percent of the association between gender-role attitudes and gender difference in cognitive functioning.

This study adds to our understanding on the importance of cultural characteristics for determining life-course outcomes such as cognitive performance later in life. In the context of global population aging and increased relative longevity for women, it demonstrated that promoting gender equality not only has beneficial effects on women’s educational and labor-market outcomes but also on their brain health in later life. Results provided a new reason for why policies promoting gender equality are crucial in particular in times of population aging. Given the current trend toward more equal gender-role attitudes among younger cohorts in many countries, we may expect further improvements in the relative position of women in terms of cognitive functioning at older age in these nations and consequently lower levels of disability among older women in these countries.

Cognition in later life, thus, cannot be fully understood without reference to the opportunity structures that socio-cultural environments do (or do not) provide. Global population aging raises the importance of understanding that gender roles affect old age cognition and productivity.

About the authors:

Eric Bonsang, University Paris-Dauphine – PSL Research University, Centre for Fertility and Health (Norwegian Institute of Public Health)

Vegard Skirbekk, Centre for Fertility and Health (Norwegian Institute of Public Health), Columbia University

Ursula Staudinger, Columbia University

This article is based on:

Bonsang E, Skirbekk V, Staudinger U, As You Sow, So Shall You Reap: Gender-Role Attitudes and Late-Life Cognition, Psychological Science (2017). https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617708634

Leave A Comment